by Daniel Payne

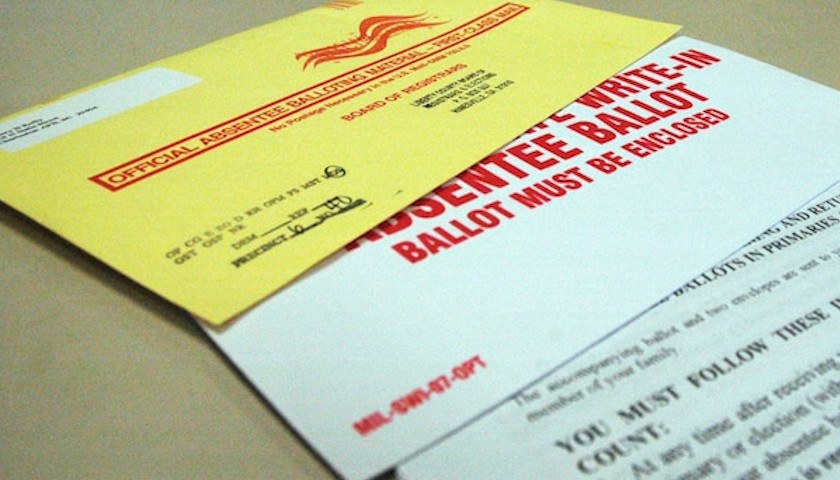

Election rules in multiple key battleground states permit voters to submit mail-in and absentee ballots without having their signatures checked to ensure the vote is valid.

Five states that have historically been competitive in presidential races — North Carolina, Iowa, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and New Hampshire — do not require signature-matching for mailed voting forms.

In some cases, state officials have explicitly codified that rule. In August, Karen Bell, the executive director of the North Carolina State Board of Elections, wrote in a memo to all local county boards that a voter’s siagnture “shall not be compared with the voter’s signature on file because this is not required by North Carolina law.”

“County boards shall accept the voter’s signature on the container-return envelope if it appears to be made by the voter,” she continued, “meaning the signature on the envelope appears to be the name of the voter and not some other person.”

“Absent clear evidence to the contrary,” she added, “the county board shall presume that the voter’s signature is that of the voter, even if the signature is illegible.”

In other cases, signature-match rules have been struck down by jurists. Judges in New Hampshire and Iowa in recent years both struck down provisions of state laws mandating signature-match policies for absentee ballots.

In New Hampshire in 2018, a judge struck down a state law ordering election officials to match a voter’s signature on the application for a mail-in ballot with the voter’s signature on an affidavit accompanying the ballot itself.

“[T]he current process for rejecting voters due to a signature mismatch fails to guarantee basic fairness,” the ruling states. “Such discretion [in signature verification] becomes constitutionally intolerable once other factors are taken into account: the natural variations in voters’ signatures combined with the absence of training and functional standards on handwriting analysis, and the lack of any review process or compliance measures.”

The ruling suggested election officials could institute a policy of reaching out to voters regarding disputed ballots in order to give them a chance to rectify the errors.

In Iowa last year, meanwhile, a district court judge struck down a portion of a state election law which mandated that a voter’s affidavit signature match his or her signature on record with the state. The judge struck down that rule both under the Iowa constitution and on procedural due process grounds.

And in Wisconsin, the state’s website declares that “election inspectors are not required … to compare the signature [of a voter] to any other record.”

“Voters should be directed to sign using their normal signature as they would sign any other official document and election inspectors should indicate the line number on which the voter is to sign,” the state says.

“The law does not require voter signatures to be legible,” the rule continues.

Reid Magney, a spokesman for the Wisconsin Elections Commission, told Just the News that the state “has never matched signatures for absentee ballots or any other voting activity.”

“There are many other security measures in place to protect the integrity of absentee voting in Wisconsin, including the use of photo ID,” he added.

In Pennsylvania, meanwhile, the state Department of State issued guidance in September directing that local election officials are not authorized “to set aside returned absentee or mail-in ballots based solely on signature analysis by the county board of elections.”

Concerns of voter fraud hang over historic mail-in election

The absence of signature-verification policies in critical battleground states raises the specter of potential voter fraud among some of the most unpredictable voting districts in the country.

Numerous politicians and commentators, including President Trump, have claimed that mass mail-in voting this year could pose a greater-than-average threat to election integrity. Attorney General William Barr said last month that the U.S. “[hasn’t] had the kind of widespread use of mail-in ballots as being proposed” this election year.

“What we’re talking about is mailing them to everyone on the voter list,” he argued on CNN, “when everyone knows those voter lists are inaccurate. People who should get them don’t get them, which is what has been one of the major complaints in states that have tried this in municipal elections.”

“And people who get them are not the right people,” he continued. “They’re people who have replaced the previous occupant, and they can make them out and sometimes multiple ballots come to the same address, with … several generations of occupants.”

Problems with mail-in ballots have been widely reported over the course of the year. In a chaotic primary season in New Jersey, there were reports of residents receiving ballots for their dead parents and hundreds of Republicans receiving Democratic primary ballots.

Millions more voters than average have turned to mail-in voting over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic out of concerns that voting in person could put citizens at risk of catching and transmitting the coronavirus.

The mass move to mail-in voting has led to a litany of logistical and procedural issues over the last several months, including many involving signature-match problems. In New York and New Jersey this year, for instance, thousands of primary ballots were thrown out due to mismatched signatures.

Voting rights activists argue that signature-match provisions are too burdensome for voters, particularly given the subjective interpretation of poll workers and the minor variations that can be observed in signatures over time. Pundits more broadly argue that voting fraud in the U.S. is comparatively rare and not likely to influence the results of a presidential election one way or the other.

Yet the vote in key battleground states this year may come down to a dispute of just several thousand ballots. In Wisconsin in 2016, for example, President Trump’s margin of victory over Hillary Clinton was just 0.77%, while in Pennsylvania it was 0.72%.

New Hampshire was an even slimmer margin, at 0.4%.

Many states with signature-matching laws dictate that voters must be contacted about any disputed ballots in order to be given the opportunity to correct them. Some states permit voters to correct disputed signatures either before the election or up until several days after it.