A joint petition has been submitted to the Surface Transportation Board (STB) on behalf of the Canadian National Railway Company (CN), Norfolk Southern Railway Company (NS) and Union Pacific Rail Road Company (UP) freight-hauling railroad companies for the purpose of modernizing annual revenue adequacy determinations of the industry’s overall financial health.

CN, NS and UP are three of the seven railroads remaining in the U.S. from the 41 that operated in 1979 designated as Class I by the STB, based primarily on the annual operating revenue of the railroad company.

The seven reportedly represent 94 percent of the industry’s revenue, 69 percent of the industry’s freight rail mileage and about 90 percent of the industry’s employees.

Their petition is based on a report by two uniquely-qualified subject matter experts retained on behalf of the railroads.

Professor Kevin M. Murphy is the George J. Stigler Distinguished Service Professor of Economics in the Booth School of Business and the Department of Economics at The University of Chicago, where he teaches graduate level courses in microeconomics, price theory, empirical labor economics and sports analytics. His bachelor’s and doctorate degrees are both in economics.

Along with numerous honors and awards, Murphy has co-authored two books, about 80 articles, and provided about as many testimonials, reports and depositions in the last four years alone.

Mark E. Zmijewski is Professor Emeritus at The University of Chicago Booth School of Business, and specializes in the areas of accounting, economics and finance as they relate to valuation, financial analysis and security analysis. His bachelors, M.B.A. and Ph.D. were all earned from the State University of New York at Buffalo, with a major in accounting and minors in economics and finance.

Professor Zmijewski’s research has focused on firm valuation and the ways in which various capital market participants use information to value securities. His work has been published nearly two dozen times, with about as numerous testimonies, declarations and other court filings and submissions in just the past five years.

The STB is an independent federal agency charged with the economic regulation of various modes of surface transportation – primarily freight rail – with jurisdiction over railroad rate, practice and service issues as well as rail restructuring transactions like mergers, line sales, line construction and line abandonments, according to the agency’s website.

The STB, created on January 1, 1996, is the successor to the former Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) which was established back in 1887. Due to the rail industry’s importance, dominance in commercial transportation, monopoly in certain regions and what many saw as high and discriminatory rates, the ICC was created to help prevent monopolies, maintain open access and regulate rates.

Reportedly, the ICC didn’t initially intend to succumb to political pressure in setting rail rates, but they had no objective basis for valuing railroad services. Wallowing in shifting subjective standards as to what were “fair” and “equitable” rates, the ICC “squeezed rail rates lower and lower in real terms.”

As Americans for Tax Reform explains:

After 20 years of ICC regulation, it was clear that inflation was causing railroad costs to surge well ahead of their rates. As a result, the industry could no longer raise the capital to maintain and replace its track or equipment. But, responding to strong political pressures, the ICC would not ease up on rail rates.

By 1917, with the start of World War I, the nation’s railroads could not handle the increased volume of freight, and leading railroads were ready to file for bankruptcy.

As a war time act, the government took over the major railroads and operated them to support the war effort. Interestingly, during that time the government increased rail rates by almost 70%. Though the government restored the railroads to private ownership after the war, under continued heavy regulation they just continued their long-term decline.

Further perspective on the history of regulation and the impact on the freight rail industry comes from The Geography of Transport Systems.

“The ICC had set rates deliberately low for farm products and higher rates for general freight, which was the most susceptible to truck competition. At the same time the railroad industry had little incentive to modernize because the ICC had to rule on major changes, and the railroads found it difficult to obtain approval to close unprofitable track and services.”

The result: “By 1960, one third of the U.S. rail industry was bankrupt or close to failure,” says The Geography of Transport Systems, and by 1975 the percent of all intercity freight movements had dropped to 35 from 75 percent in 1920.

In addition, the rate of accidents increased dramatically, taxpayer subsidies had climbed to $250 million per year to keep some railroads running, and Washington policymakers began talk of nationalizing railroads.

In 1976, Congress took a first step to rehabilitate the railway system by enacting the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act – also known as the 4R Act – which eased regulations on rates, line abandonment and mergers.

The 4R Act was followed up with the Staggers Rail Act of 1980, widely recognized for its successful deregulation by repealing much if the ICC’s regulatory authority.

While the ICC retained authority to control rates in abusive circumstances, for the first time, railroads could enter into unregulated and private contracts with shippers with market-driven pricing for the railroad’s services.

As stated in the petition, one of the hallmarks of the Staggers Act was the desire of Congress to “treat the American railroad industry as any other business.”

Congress required that the STB measure annually the financial health of the rail industry and assist each railroad in achieving “revenue adequacy.”

While the STB says it “relies on evidence-based policy and program decision-making,” the petitioning railroads maintain that the STB attempts to fulfill their statutory responsibility with flawed and incomplete data.

The Problems with the Current System in Determining “Annual Revenue Adequacy”

The Staggers Act requires the STB “to maintain standards and procedures for making annual determinations of whether the earnings of each of the Class I railroads is sufficient to attract capital,” according to the Transportation Research Board (TRB) of the National Academies.

Railroads, a capital-heavy industry, compete for capital to purchase, operate and maintain their infrastructure and equipment with any number of other private companies.

As a result of the study published in 2015, TRB actually suggests STB discontinue issuing the annual reports and replace them with periodic studies of economic and competitive conditions in the industry due to the reports having become “ritualistic while offering little substantive information for regulators and policy makers.”

This is an issue that has gone on for years, as evidenced, in part, by the study’s authorization by Congress in 2005 and the ultimate funding appropriation for it in 2012.

The petitioners ask if the STB’s annual revenue adequacy determinations are designed so that it may fulfill its statutory duties in accurately measuring and properly promoting railroad revenue adequacy, to which their answer is no.

The first issue is that the definition by Congress for revenue adequacy, per 49 U.S.C. 10704(a)(2), is that rail carriers’ revenues should support “the infrastructure and investment needed to meet the present and future demand for rail services and to cover total operating expenses, including depreciation and obsolescence, plus a reasonable and economic profit or return (or both) on capital employed in the business.” (emphasis added)

The second issue is in using an “accounting” versus “economic” profit or return.

As Professors Murphy and Zmijewski point out, “The methodology used by the Board which relies on book value of assets cannot reveal whether railroads will be able to attract investors in the future. In deciding whether to replace or upgrade track, for example, a railroad does not ask whether the return on book value of existing track exceeds the cost of capital, but whether it can earn an adequate rate of return (above its cost of capital) on the replacement cost of that track.”

They also point out that the advantage for the STB, and the ICC before that, in using historical costs is that it is easy both to calculate and to obtain the necessary data from the financial submissions of the railroads to the STB or third-party sources.

Third, the way the STB treats deferred taxes “is contrary to basic valuation principles and amplifies the distortions from using account rate of returns to measure the financial health of the railroad industry.”

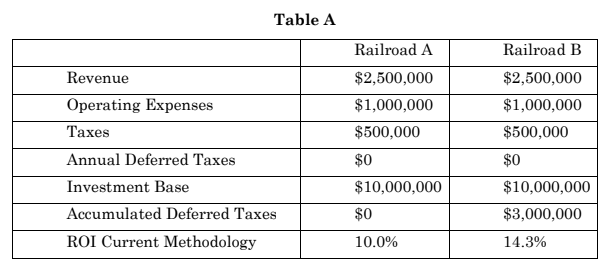

The petitioners use a table to demonstrate how the result of a deferred taxes approach “makes no economic sense.”

The STB’s treatment of deferred taxes also creates practical problems when changes to corporate tax rates can “produce ridiculously inaccurate measurements of financial health,” as occurred with The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

Fourth, the STB makes its annual determination in isolation by calculating an average return on investment (ROI) for all Class I railroads and then compares each railroad’s ROI with an estimate of the industrywide cost of capital.

Petitioners’ Proposed Solutions for Determining “Annual Revenue Adequacy”

Unlike the TRB which recommended abandoning the practice altogether, the petitioners, through their experts, make recommendations for changes to the STB’s methodology, which it inherited decades ago from the ICC.

First, the STB must recognize that in order for railroad carriers’ revenues to be considered “adequate,” they must be sufficient not just to cover operating expenses and infrastructure costs, but also to earn a profit that is both reasonable and “economic” based on replacement cost of asset values. And, that profit has to be above the cost of capital, not equal to it.

STB’s interpretation that “revenue adequate” is when ROI equals the cost of capital, is inconsistent with the requirements of 49 U.S.C. 10704(a)(2) and reflects no economic profit to the railroad at all, much less a reasonable amount.

Second, the STB “has long recognized that replacement costs are conceptually superior to book value,” the petitioners say, but the STB maintains that it is too difficult to implement a replacement cost solution.

The petitioners suggest a comparative approach to other S&P 500 companies as to their book value compared to their cost of capital to give STB marketplace information. The petitioners say that this approach, while being “a more modest path,” would incrementally improve the accuracy and reliability of STB’s methodology.

“While replacement costs would be superior, use of this marketplace information would improve the accuracy of revenue adequacy determinations,” according to the petitioners.

Third, the petitioners, in line with the approach originally proposed by the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), encourage a flow-through approach for the treatment of deferred taxes.

Citing DOT’s five reasons why the flow-through approach is superior, the petitioners said the STB still rejected DOT’s proposal.

Professors Murphy and Zmijewski say that eliminating the effect of deferred taxes “is consistent with basic valuation principles,” which the petitioners say is “echoed by virtually every economist to have testified on this issue.”

The petitioners maintain that the comparison proposal is, even with its numerous calculations, “easily implemented and verifiable.”

The information, obtained from public sources that are reliable and verifiable, would be gathered by and mechanically applied per STB’s standards by the railroad companies.

Finally, and most significantly, the railroads’ financial performance should be measured against other companies that compete for capital – namely the S&P 500.

The concept is not new, in that the 2015 TRB study also urged STB to “obtain a richer set of information” to determine “whether a railroad’s profits are consistently outside a reasonable band of profitability that characterizes many other industries over a business cycle.”

Professors Murphy and Zmijewski looked at S&P 500 companies using STB’s definition of Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) and Cost of Capital (COC) and compared it to that of the railroad industry over a period of 14 years from 2006 to 2019.

For comparison purposes, the professors’ evaluation broke the S&P 500 companies into three groups: (1) excluding railroads, financial institutions and real estate companies; (2) companies in the industrials sector, excluding railroads; and (3) railroad customers.

The professors also used two alternative measures of financial performance, which was detailed in their report.

The data was then presented in several tables, for a more straightforward and easier comparison.

Using their benchmarked analyses, the professors demonstrate that “the financial performance of the railroad industry as a whole and each of the seven railroads was well below the financial performance of companies operating in competitive (unregulated) markets of the 2006-2019 period.”

“Specifically, using two alternative measures of financial performance and three benchmarking groups,” the professors found over the 14-year period, “the financial performance of the railroad industry and the seven railroads fell well below the median and mostly in the bottom quartile of the financial performance of all three benchmarking groups.”

In the future, if the railroads were to exceed the median for benchmarking groups, the professors recommend that the STB first investigate whether the cause is due to greater efficiency, benefits from risky investments, increases in demand that exceeded expectations or other procompetitive reasons.

If the STB rules out procompetitive reasons and concludes there is a lack of competition available to some shippers or geographic areas, the professors recommend the STB perhaps make it easier for shippers to challenge potential non-competitive pricing.

Finally, Murphy and Zmijewski suggests the STB not penalize especially efficient railroads and thereby create distortions in competition if additional regulation was imposed on one railroad and not others. Instead, the professors say the STB should “look at the industry as whole in evaluating whether there is a basis for considering additional regulation in response to potential lack of competition.”

If the STB determines that such regulation is warranted, Murphy and Zmijewski say it should be imposed on the entire industry and not just on individual railroads.

The full text of the petition can be read here.

– – –

Laura Baigert is a senior reporter at The Tennessee Star.