by Martha Njolomole

President Joe Biden’s new $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief proposal includes a surprising provision: raising the federal minimum wage to $15.

The fight for a higher minimum wage is not new, although it has been intensified by current events. The idea, more specifically, is to provide a “living wage.” Proponents argue that, currently, minimum wage workers cannot afford basic living expenses. But even if one assumes for the sake of argument that this is true and sets aside the fact that small businesses are already on the brink of collapse, it’s impossible to determine one suitable “living wage” for all parts of a vast and diverse country like the United States.

Costs of Living Differ Enormously

Beginning January 1 of this year, about 24 states have raised their minimum wage. According to the Economist, even after these 24 states raised their minimum wage, only three states are offering a minimum wage above the state’s “living wage.” A living wage, in this case, is defined as “a theoretical income level in 2020 that allows an individual to afford adequate shelter, food, and other basic necessities.”

One important trend here is that out of the 24 states, only three states—New York, California and Massachusetts—require a living wage of $15 or higher. In the rest of the country, the “living wage” is actually less than $15 an hour.

Additionally, the gap between states is staggering. Take, for instance, Arkansas and New York.

Arkansas has a living wage of between $10 and $11 per hour. New York, on the other hand, has a living wage of $15 and $16 per hour. This is not surprising, considering the fact that living in New York is much more expensive than living in Arkansas.

But it does make it hard to imagine any good reason the two states should have the same minimum wage. What would happen if Arkansas businesses were forced to offer the same level of wages as businesses in New York?

Businesses in Arkansas would see their labor costs relative to levels of income rise significantly, a larger increase than New York businesses would face. Arkansas businesses would have to offset this rise in costs.

To the extent that they can, they will raise prices of goods and pass those costs on to customers. But it is more likely that businesses in states like Arkansas will be forced to cut jobs or reduce the hours of workers, and likely at a higher margin compared to high income, high-cost states.

It’s a simple fact that income levels in most low-cost states cannot support a $15 minimum wage.

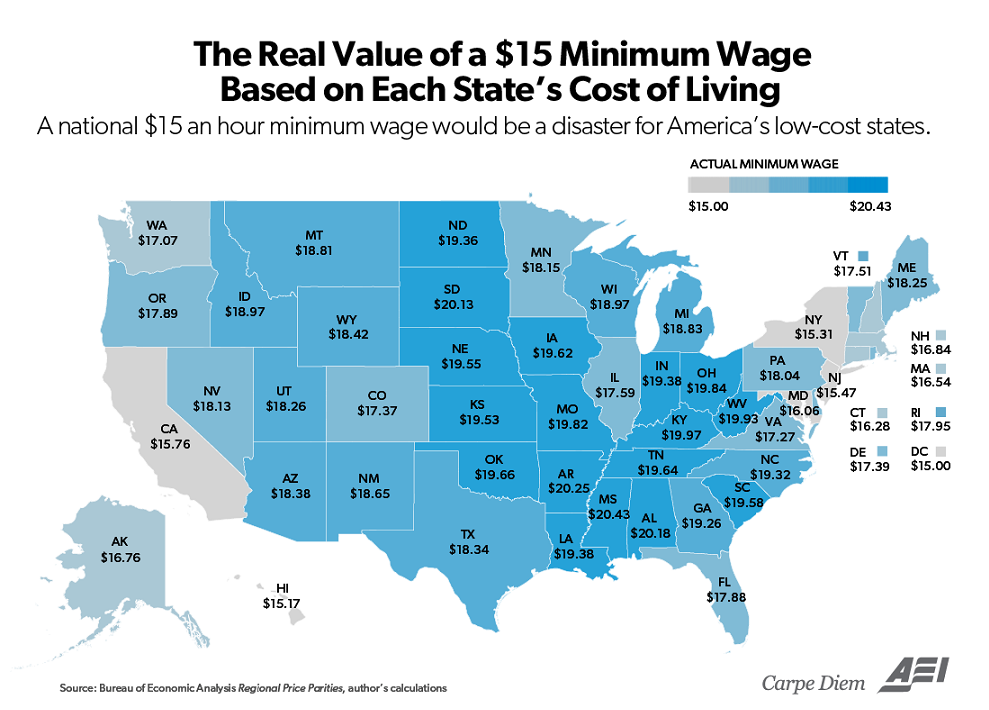

The American Enterprise Institute calculated what a federal $15 minimum wage effectively amounts to in each state. By indexing each state to DC’s cost of living (which happens to be the highest in the nation), a $15 minimum wage translates to a remarkably higher wage in most states. In low-income, low-cost states like Alabama, a $15 minimum wage had an effective value of $20.

This means the effects of raising the federal minimum wage will be more pronounced in low-cost states compared to those of high-cost states.

Even State Averages Obscure Local Differences

But even at the state level, large differences exist between different local regions. For most states, living in metropolitan or big cities is more expensive compared to living in rural areas. So, when we talk about averages, state “living wage” figures tend to skew these differences in local living costs.

So, while a state like Minnesota requires a $12 per hour living wage, that number fluctuates depending on the specific area you choose to look at.

According to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, for example, Minnesota, Hennepin County in 2019 had the state’s highest per-capita personal income at $76,552. This is more than twice as much as the the county with the lowest per capita personal income. These regions should certainly not be subjected to the same minimum wage level.

Neither should New York City and the rest of New York State.

In 2019, New York City had an average income per person of $197,847. Yet New York State’s average per capita personal income is about $72,000. Additionally, the state has about 39 counties with income below $50,000 and just 23 with incomes above $50,000.

One-Size-Fits-All Policies Do Not Work

If there is one fact that economics can teach us, it’s that “one size fits all” policies do not work. Why? Such policies assume all human beings have on average the same preferences, same opportunity costs, similar level of skill, and the same dedication to achieving their goals.

However, even minimum wage workers are very diverse.

The minimum wage workforce is made up of young teenagers that want to do part-time work to gain experience; entry workers that happen to be on their way to climbing up the economic ladder; workers that for various reasons prefer to work part-time; low skilled individuals who are, for lack of a better word, unluckily stuck in low-paying, less-productive sectors of the economy.

For some reason, this last group is the one always used as a base for what should be done. But data from the Bureau of Labor statistics show that the minimum wage workforce is made up mostly of young, less educated part-time workers who are less likely to be married or have a family. Furthermore, the population of workers earning the minimum wage is very small compared to the total workforce and has been shrinking.

These are groups of people that cannot be lumped together—and what helps one group does not especially help the other.

Older low-skilled workers, for example, could potentially benefit more from training initiatives that help to close the skills gap so they can be paired up with better paying jobs. They can, furthermore, be helped by loosening laws that restrict entry into lucrative occupations. Young workers, on the other hand, could be helped if the minimum wage was lowered or abolished, and so would small businesses.

There are countless fundamental differences within our economy that a one-size-fits-all federal minimum wage can never take into account.

– – –

Martha Njolomole is an Economist at the Center of the American Experiment, with a Master of Arts Degree in Economics from Troy University. Her research interests include public policy with a focus on economic policy.

Photo “Raise the Wage Protest” by The All-Nite Images. CC BY-SA 2.0.