by Steve Miller

CALIFORNIA CITY — California’s precariously out-of-date hybrid power grid can’t handle the state’s growing amounts of solar and wind energy coming online, with system managers already forcing repeated cutbacks in renewables and a continued reliance on conventional energy to keep the grid stable, according to state data.

The shortcomings of the transmission grid, which energy consultants in this bellwether state have warned about for years, raise the prospect that marquee products of the growing battery economy such as electric vehicles – “emission free” on the road – will be recharged mainly from traditional electricity-generating power plants: energy from fossil fuels, some of it from out of state.

Writ large, the transmission problem threatens the zero-carbon future envisioned by green advocates nationwide. “We’re headed toward duplicate systems whose only benefit is to permit the occasional use of ‘clean power,’” said Grant Ellis, an independent electrical engineering consultant in Texas.

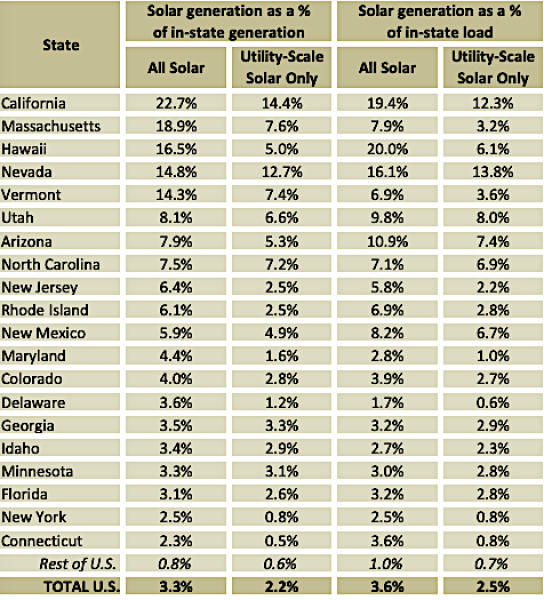

California, along with the rest of the desert Southwest, is adding solar and wind installations at a rapid pace. The state is projected to add four gigawatts of utility-scale solar energy this year alone, enough to power 2.8 million homes. The question is whether that’s going to be enough.

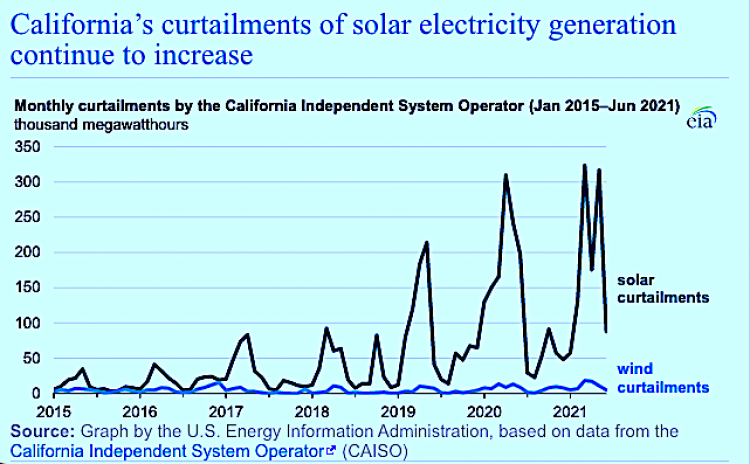

So-called “curtailments” of renewable power have become much more frequent for the state’s blackout-prone power grid because the state hasn’t constructed enough transmission lines, transformers, poles, and other infrastructure to keep up. The amount of renewable energy curtailed in California tripled between 2018 and 2021, according to operator statistics.

On top of the conventional power often deployed in its stead, that renewable power was thus wasted, since there is no place yet to store it. The state curtailed 596,175 megawatt hours in April, or 596,175 million kilowatt hours, according to several calculators. With 10,715 kilowatt hours the average annual electric consumption of a home in the U.S. in 2020, as calculated by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, California’s curtailed wind and solar energy in April could power 55,000 homes for a year.

The cutbacks mean that electric power generation falls back on nuclear and hydroelectric power, natural gas, and other more traditional sources, which provided nearly 60% of California’s electric generation last year.

The state also imported 30% of its electric energy last year from other states – 9.5% of it from coal, most of it from the Intermountain Power Project in Utah.

The curtailments come at a crucial time in what the Biden administration insists is a “transition” from a fossil fuel-driven country to one that relies on renewable energy to save the planet from what believers warn will be a climate-change disaster.

Eric O’Shaughnessy, a renewable energy consultant who has worked with the federally funded Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, blames a stalemate between renewable energy providers and electric system operators over who will pay for any infrastructure buildout.

“The system operators say, ‘We need this huge investment, and you are going to have to pay it,’ and the solar developer believes everyone should pay,” O’Shaughnessy said. Then politics comes into play “and that project gets shelved.”

The government’s answer is more taxpayer funding for transmission, although it will take at least 10-15 years to develop a new project, according to the Transmission Agency of Northern California, a group of publicly owned utilities in the state.

That’s been tried before: In 2011, the Obama administration created the Rapid Response Team for Transmission, which included five projects in the West. One is under way, while the others have been cancelled or delayed. A website created to track the projects has been defunct for years.

The messy process of connecting solar and wind plants to the grid is made more complicated by a maze of committees, panels, and lawyers that need to weigh in on the specifics of each project.

“If an energy company in California wants a transmission line, it has to go to a public utility to build it, and to the California Energy Commission and a bunch of other commissions,” said Rajat Deb of energy consultant LCG. “And the cities also have to approve in some cases, so it takes all that to get a transmission line. That’s a lot of hoopla you have to go through.”

There is less resistance to building individual solar plants in distinct locations than to transmission lines, often due to the wider geography needed for the latter. And so more solar plants get built while transmission projects languish.

Still, the state aims to have a carbon-free electric grid by 2045, a goal set before President Biden took office and declared 2035 as a national objective. With its goal in mind, California has imposed restrictions and requirements that have adversely impacted businesses, home builders, and car makers as well as taxpayers, who pay the highest prices for fuel and the third highest rate for electricity in the U.S., behind Hawaii and Alaska. Electricity prices for residential customers in California have increased 19% in the past year compared with 7% nationally.

Gov. Gavin Newsom issued a 2020 executive order mandating that by 2035, all new vehicles sold in the state must be zero-emission. If that goal is reached, it would add a crushing demand to the state’s electric grid, according to some projection models.

With multibillion-dollar development of massive wind farms and solar plants outpacing transmission capacity, the number of miles of new high-voltage transmission has declined over the last decade from an annual average of 2,000 miles nationally from 2012-2016 to an average of just 700 miles from 2017-2021, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

A report issued by the department this year, titled “Queued Up…But in Need of Transmission,” acknowledges the problem: “A large amount of potential clean power capacity is struggling with the wait times and costs of connecting to the transmission grid. …”

The Energy Department’s advocacy of de-carbonization includes technical reviews by representatives of big solar concerns as well as big oil corporations, most of the latter of whom also are investing in renewables.

The department declined an interview request, but Becca Jones-Albertus, director of its Solar Energy Technologies Office, wrote in an email exchange: “DOE is working to improve transmission through the Better Grid initiative, and there are other tools available now to alleviate the long wait times and costs associated with connecting to the grid.”

Jones-Albertus was referring to the Building a Better Grid program, launched in January as part of $20 billion in federal funding for upgrading and developing transmission nationwide. She did not respond to a question regarding the nation’s longstanding lack of ability to transmit solar and wind energy.

Jones-Albertus also downplayed the necessity of transmission in meeting the current government’s green goals.

“While transmission expansion takes time, energy storage, active generation management, and demand flexibility are ready for deployment to help the nation achieve an emission-free electricity grid by 2035 without increasing energy prices,” Jones-Albertus said in the email. She was referring to the Biden administration’s nationwide push for “carbon pollution-free electricity by 2035,” according to a 2021 executive order from the White House.

Encouraged by green advocates, state and federal lawmakers have plowed money into renewable sectors with grants, tax breaks, loans, and other funding mechanisms while often leaving the “how to” of energy transmission to fend for itself.

This year transmission got more funding, including $2 billion in loans for infrastructure in the Democrats’ newly enacted Inflation Reduction Act.

Today, 61% of electricity in the U.S. comes from coal, petroleum, natural gas, and other sources. Without transmission resources – power lines that cut through swaths of land, both public and private, or the much more expensive underground cables – there is little chance of a dramatic reduction of fossil fuel electricity.

The recent rush into renewables has created a situation where solar and wind developers can end up with plants that have to wait a minimum of three years before securing approval to sell energy.

“There are a lot of renewable projects waiting in these lines requesting to connect to the system and they are not getting connected,” said Elise Caplan, director of electricity at the American Council on Renewable Energy.

“The vast majority of transmission has been local,” Caplan added. “The U.S. has done a bad job of building these critical larger-scale [projects].” Her group is among a growing number of renewable energy advocates asking the feds to examine the transmission problem at the local level.

Rajat Deb, the LCG consultant, voiced the frustration of green advocates.

“I am an environmentalist in my heart and the biggest problem we have right now is global warming,” he said. “I have been working on this for 40 years and nothing happens. And while they are talking about this, all these [non-governmental agencies] are making money and the state and federal government is spending money. Where is that going?”

– – –

Steve Miller is a writer for RealClearInvestigations.