by Lloyd Billingsley

Fort Hood, Texas, is named after John Bell Hood, a West Point graduate and Confederate general. The Army wants to rename the base after the late General Richard Cavazos, a hero of the Korean and Vietnam wars. This selection bypasses qualified candidates with a history on the base, such as Lieutenant Colonel Juanita Warman.

An expert in post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury, Warman received an Army Commendation Medal for service at Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany, the facility where soldiers injured in Afghanistan and Iraq received treatment before returning stateside. Warman loved her work and volunteered for flights to Iraq to care for soldiers.

In 2009, Warman was posted to Fort Hood, where American troops were departing for duty in Afghanistan. She arrived on November 3 and two days later U.S. Army Major Nidal Hasan shot Warman dead. She was 55, with two children, and not the only woman to perish that day.

Amy Sue Krueger, born in 1980, enrolled at the University of Wisconsin but after 9/11 enlisted in the Army to join the war on terrorism. The mental health specialist volunteered for a mission to Afghanistan and in October 2009, Staff Sergeant Krueger, 29, arrived at Fort Hood. On November 5, Hasan shot her dead. The shooter seemed to have a preference for women.

Francheska Velez was the daughter of Juan Velez, a Colombian immigrant who tried to join the U.S. military but didn’t meet the requirements. Francheska told him “Papi, lo voy hacer,” and duly joined up. Private Velez was deployed to Iraq but got pregnant and returned to begin maternity leave. At Fort Hood on November 5, 2009, Nidal Hasan targeted the 21-year-old, who yelled “My baby! My baby!” Hasan shot Velez in the chest and her unborn child was never counted among the 13 murder victims.

“What I don’t understand is how this demented man could do this,” Juan Velez told reporters. “How could she die at the hands of her own people?”

That calls for background on the shooter, and his rise through the ranks.

Born in 1970 to Muslim immigrants, Nidal Malik Hasan graduated from Virginia Tech and in 2003 completed psychiatry training at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland. Hasan served his residency at Walter Reed Medical Center, where instructors cited his “pattern of poor judgment and lack of professionalism.”

As the report “Lessons from Fort Hood” notes, during his residency and post-residency fellowship, Hasan demonstrated evidence of violent extremism, called himself a “soldier of Allah,” and wrote papers defending Osama bin Laden. Two officers described Hasan as a “ticking time bomb” but the Army promoted Hasan and considered him competent to counsel soldiers.

On December 17, 2008, Hasan visited the website of radical Islamic cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, an al-Qaeda leader. Hasan sent a message to al-Awlaki and another on January 1, 2009. The messages were acquired by the FBI Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) in the San Diego Field Office. In early January 2009, the emails were sent to the FBI’s Washington field office and FBI headquarters.

In May 2009, the Army promoted Hasan to major and two months later sent him to Fort Hood. On May 31, Hasan again emailed al-Awlaki about suicide bombers whose “intention is to kill numerous soldiers,” and “save his fellow people.” As Hasan explained, “this logic seems to make sense to me.” In another email to al-Awlaki, Hasan wrote, “Please keep me in your Rolodex in case you find me useful, and please feel free to call me collect.”

The next month, the FBI’s Washington field office emailed the San Diego office: “Given the context of his military and medical research and the content of his, to date, unanswered email messages from al-Awlaki, WFO does not currently assess Hasan to be involved in terrorist activities.” The FBI then dropped the case until November 5, 2009.

That day the soldier of Allah deployed an FN Five-seveN handgun fitted with laser sights, and carried a .357 magnum in reserve. At the Soldiers Readiness Center, Hasan slipped behind a desk, bowed his head in prayer, then stood up, yelled “Allahu akbar,” and began firing. At first he fired into the most densely packed areas then began targeting individual soldiers, including Captain John P. Gaffney, Specialist Frederick Greene, and civilian physician assistant Michael Cahill.

Hasan shot Major Eduardo Caraveo, Staff Sergeant Justin Michael DeCrow and Specialist Jason Dean Hunt, who took a fatal bullet in the back. Hasan gunned down Privates First Class Aaron Thomas Nemelka Michael S. Pearson, and Captain Gilbert Russell Seager. Hasan’s head shot took out Pfc. Kham See Xiong of St. Paul, Minnesota.

The wounded included Sgt. Alonzo Lunsford who took seven bullets from Hasan, including shots in the head and abdomen. His fellow soldiers commandeered a table and rushed Lunsford to triage. Hasan also grazed the right side of Staff Sgt. Shawn M. Manning and shot him in the left upper chest, left back, lower right thigh, upper right thigh, and right foot.

And so on, for more than 30 others, including civilian police officer Kimberly Munley. Unlike the other victims, Munley was armed. She managed to wound the man FBI bosses claimed was not involved in terrorist activities.

Consider also the response of the composite character president David Garrow described in Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama.

Barack Obama, commander-in-chief of U.S. Armed Forces, failed to mention a single victim by name. The president called the mass murder “incomprehensible” and a “tragedy,” not an act of terrorism or an atrocity. The president also spared Nidal Hasan any open condemnation. His victims included African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians, but the president raised no possibility of racist motivation.

The Defense Department called the attack “workplace violence,” not even “gun violence.” This was an effort to avoid portraying the attack as terrorism or combat, and to deny the victims the medals and benefits they deserved. In 2014, Obama declined to meet with Sgt. Alonzo Lunsford. Those are tough acts to follow but Vice President Joe Biden was up to the task.

“Jill and I join the President and Michelle in expressing our sympathies to the families of the brave soldiers who fell today,” Biden said in a statement. “We are all praying for those who were wounded and hoping for their full and speedy recovery. Our thoughts and prayers are also with the entire Fort Hood community as they deal with this senseless tragedy.” The Delaware Democrat failed to name any soldiers who “fell,” and did not openly condemn the terrorist who murdered them.

In his August 2013 court-martial, Hasan admitted he was the gunman and told a judge he killed the soldiers to protect Muslims and Taliban leaders in Afghanistan. On August 23, 2013, the jury found him guilty of all 42 counts and sentenced him to death. The sentence has not been carried out. Nidal Hasan was able to “kill numerous soldiers” and keep his own life.

After Biden’s disastrous withdrawal last year from Afghanistan, with 13 American troops dead from a terrorist bomb, Hasan proclaimed. “We have won!!!” This is what happens when the U.S. military retains a self-acknowledged jihadist. This is what happens when the FBI looks the other way at an obvious threat. And to answer Juan Velez, this is why Francheska Velez, Amy Sue Krueger, and Juanita Warman were killed at Fort Hood.

In 2022 moving forward, it’s all about memory against forgetting. Remember November 5, 2009, the deadliest mass shooting at a U.S. military facility and the most horrific terrorist attack on U.S. soil since September 11, 2001. The murder victims, including three women, were passed over for the renaming of the base where they perished. If their fellow soldiers, friends and loved ones thought that was part of a shameful coverup, it would be hard to blame them.

– – –

Lloyd Billingsley is the author of Hollywood Party and other books including Bill of Writes and Barack ‘em Up: A Literary Investigation. His journalism has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, the Spectator (London) and many other publications. Billingsley serves as a policy fellow with the Independent Institute.

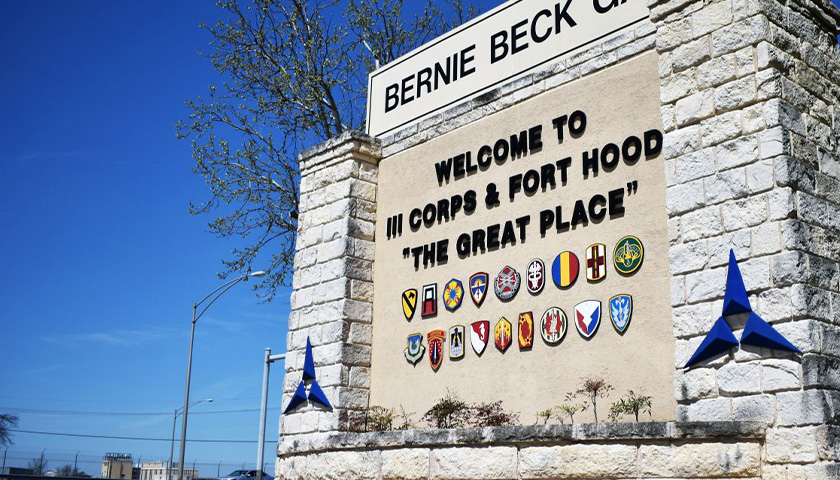

Photo “Fort Hood” by U.S. Army.