by Dan Byers

Famed energy historian and author Dan Yergin recently remarked that the “energy divorce” between Europe and Russia is speeding up. With each passing day of the war, Yergin observes, the pertinent question becomes less about if it happens and more about when it happens—and which side initiates it—the EU through expanded sanctions, or Vladimir Putin as a means to weaponize Russia’s energy leverage over the continent.

To state the obvious, cutting the cord will take years and be very painful, but at this point the national security and moral imperatives necessitating the divorce are undeniable. Europe is largely united in this effort and appears open to considering all options, from accelerated deployment of energy efficiency and renewable energy deployment to diversification of oil and natural gas supplies, and even emergency support for disfavored resources such as coal and nuclear power (concerning side note: the EU is currently expected to close a whopping 82 gigawatts of coal, lignite, and nuclear power between now and 2030—the supplies of which are largely free from Russian influence).

As the closest thing to a global energy superpower, the United States is poised to help its European allies in lots of ways. In March, the White House and European Commission issued a joint energy security statementsetting forth a framework aiming to do just that. The centerpiece of this announcement was a commitment by the U.S. to deliver an additional 15 billion cubic meters (bcm) of liquified natural gas (LNG) to Europe in 2022, increasing to 50 bcm annually “until at least 2030.”

While the path to meeting these commitments in the short run remain unclear, we applaud the Biden Administration’s effort and know that, with supportive policy signals, the U.S. energy industry is eager to unleash production and export of abundant oil and gas supplies that can displace Russian energy.

There is, however, hesitation in some political circles regarding this effort due to concerns that it could lead to backsliding on climate progress. While it is generally accepted that over the long-term, emissions from fossil fuel consumption can be greatly reduced through the utilization of hydrogen and carbon capture technologies, conventional wisdom is that emissions would increase in the short-term. It is here that an unappreciated paradox exists: by displacing dirtier Russian energy, increasing U.S. oil and natural gas exports to Europe can actually reduce greenhouse gas emissions in Europe.

The remainder of this piece summarizes the plentiful data points in support of this case. First, as our friends at Citizens for Responsible Energy Solutions first highlighted in a recent white paper, a 2019 Department of Energy analysis found that natural gas pipelined from Russia to Europe’s electricity sector has 41 percent higher life cycle emissions than American LNG shipped to Europe from the Gulf of Mexico (technical note: this comparison is based on a 20-year global warming potential (GWP) for methane).

Based on DOE’s modeling, we can then calculate an estimate of the life-cycle emissions benefits that Europe could achieve simply by replacing Russian natural gas imports with U.S. LNG. For example, if the US-EU goal of delivering an additional 15 bcm of LNG in 2022 is met, emissions would be reduced by nearly 22 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (mmtCO2e). If the longer-term goal of an additional 50 bcm is achieved, the reductions would total 73 mmtCO2e. This is nothing to sneeze at—for comparison, it represents the equivalent of taking 16 million cars off the road, all the while depriving Putin of a key cash cow that is funding his gruesome war.

As impressive as those benefits are, they may significantly understate the emissions advantage of EU supply diversification. That’s because new data released by the World Bank earlier this month show the environmental advantage of U.S. energy widening even further in the years since DOE’s analysis was first published.

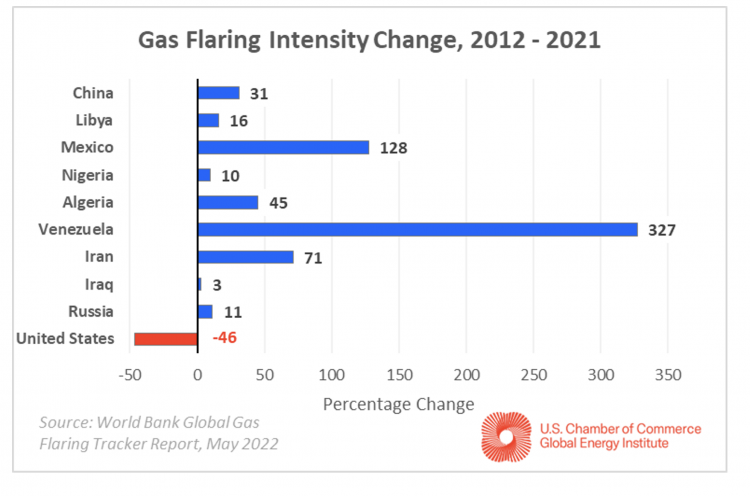

In cooperation with the Payne Institute at the Colorado School of Mines, the World Bank published the 2022 Global Gas Flaring Tracker Report, which provides a wealth of data on flaring associated with oil and gas production. According to the report, 2021 global emissions from flaring rose slightly, led by increases in Russian, Iran, Mexico, and Libya. In contrast to these unfortunate global trends, the report singles out the United States as a lone bright spot:

“Considering again the top 10 flaring countries on a volume basis, Russia, Iraq, the United States, Nigeria, and Mexico have all committed to the World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 (ZRF) Initiative, which commits governments and companies to (a) not routinely flare gas in any new oil field development, and (b) to end routine flaring in existing oil fields as soon as possible and no later than 2030. However, over the past decade, only the United States has successfully improved the flaring intensity of its oil production.” (Emphasis added)

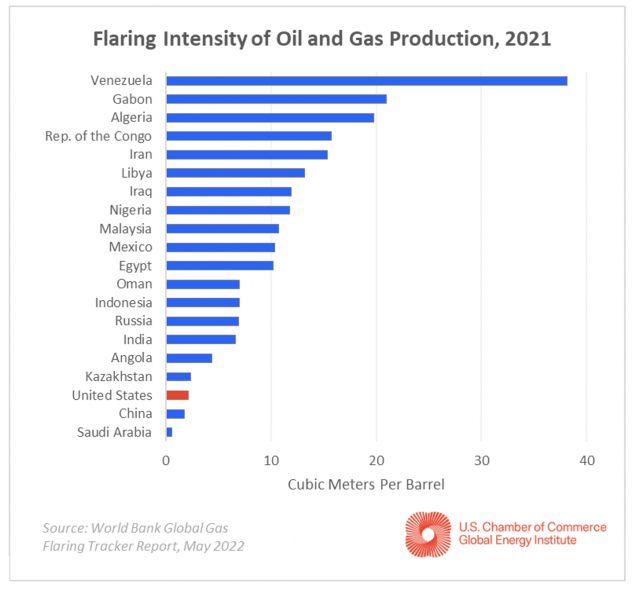

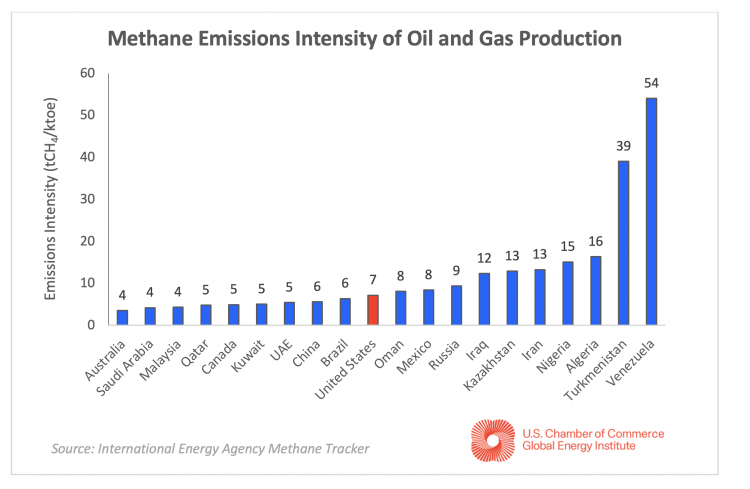

Adding to the confidence in these World Bank’s satellite-derived estimates is their consistency with the International Energy Agency’s Methane Tracker, which includes fugitive methane emissions as well as those generated from flaring. IEA estimates that the methane intensity of oil and gas production in Russia is 30 percent higher than in the United States. Emissions in Iran are 85% higher for each unit of energy produced, and Venezuela is off the charts at 652% higher.

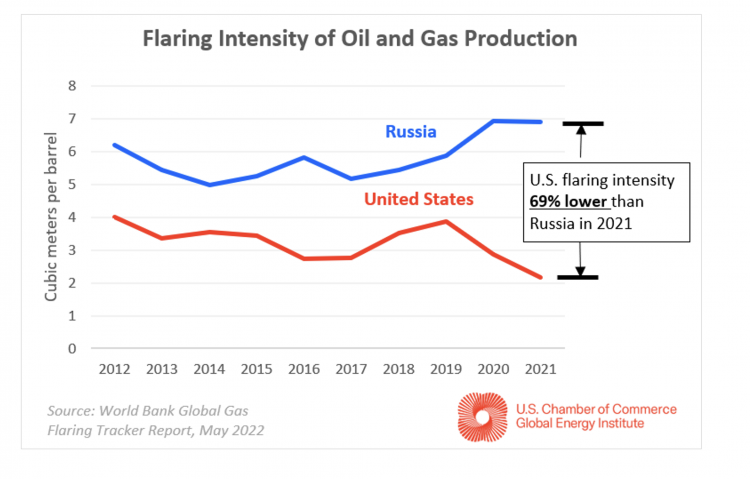

Moreover, as shown in the chart below, U.S. progress in reducing flaring is accelerating, falling 44 percent since 2019 to a level that is now 69 percent lower intensity compared to Russia. These trends are poised to improve further, as U.S. oil and gas producers work to continue reducing emissions throughout their supply chains and additional pipeline takeaway capacity reduces the need to flare for safety reasons.

One final technical note: opponents of expanded U.S. energy production may argue that the emissions benefits discussed above could be undermined if Russia can make up for lost European sales by finding other buyers of its emissions-intensive energy. While this scenario may occur to some extent, experts believe they will encounter significant difficulty in replacing much of it.

Regardless, the longer-term bottom line remains unchanged: with some of the cleanest energy production in the world, progressively reducing Russia’s global energy market share through expanded production and export of U.S. oil and natural gas will deliver short-term benefits to energy security and the environment alike.

– – –

Dan Byers is vice president for policy at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Global Energy Institute.